Fueling for an ultramarathon

Published: 25.04.2024

In this article, we delve into energy and hydration strategies related to ultramarathon races with a trail running coach Jeremy Inabnit. Jeremy participated in the Kainuu Trail trail running event last year and completed the United Endurance Sports Coaching Academy (UESCA) ultramarathon coaching certification last fall. We highly recommend everyone participating in the Kainuu Trail or any other trail running events to explore this highly informative and practical piece. Enjoy your reading and good luck for this summer's trail running events!

Jeremy at the Kainuu Trail 2023 (Photo: Hannu Huttu / Kainuu Trail)

Ultramarathons have been called eating contests, and for good reason. A runner’s nutrition strategy, or lack of, can have a major impact on how well his or her race day plays out. Here are some basic guidelines that can be considered as you prepare for your next race.

PRE-RACE NUTRITION AND HYDRATION

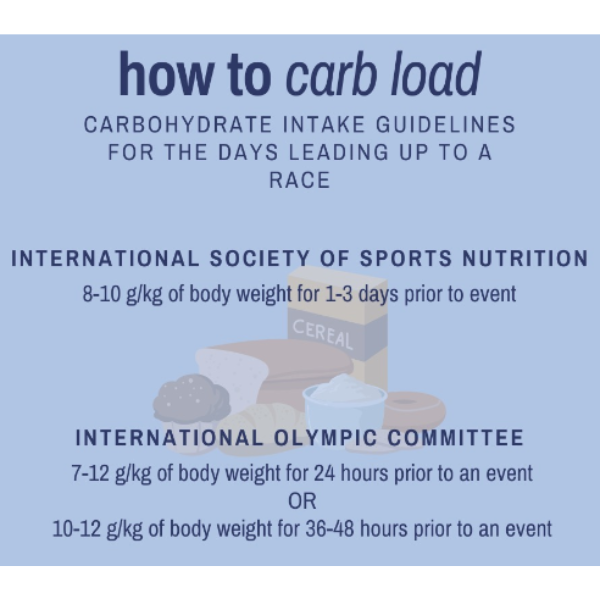

CARB LOADING

Increasing carbohydrate intake to 10-12 grams per kg of bodyweight for 36-48 hours prior to an event has proven to be a useful strategy for topping up muscle glycogen stores. For example, a 70 kg runner would consume 700-840 grams of carbohydrates in the final days leading up to a race. Some may also find it helpful to reduce fiber intake to prevent any stomach distress on race day. And while protein and fat can and should still be consumed, perhaps during these few days quantities of these macronutrients can be scaled back a little bit to keep the total calorie count from being excessively high. This can also reduce some of the load placed on the digestive system.

HYDRATING AND FUELING BEFORE THE RACE

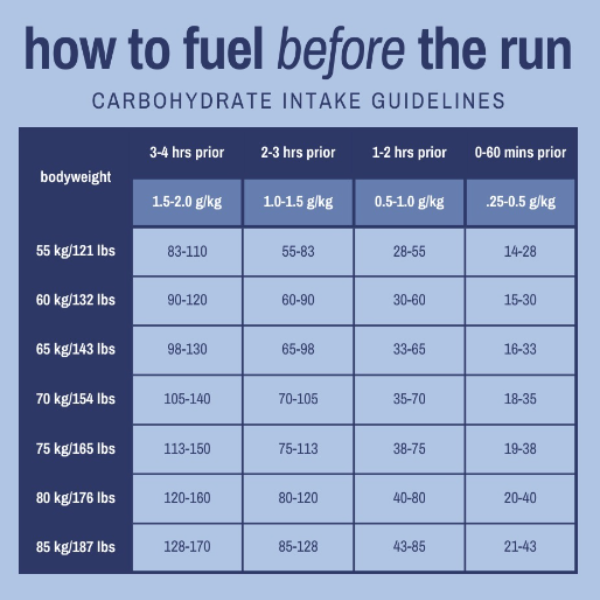

Generally, food that is consumed closer to the start of the race should be in smaller portions than meals consumed earlier so that digestion does not interfere with the race. Small to moderate amounts of protein and fat can be consumed, but for pre-run fueling, it’s going to be the digestion of carbohydrates that makes the biggest impact in the following hours. The chart below shows how many grams of carbohydrates should be consumed prior to a race based on a runner’s bodyweight.

Chart 1: Check out in Instagram

It can be useful to have a couple of different meal options in mind in case your eating schedule needs to change. For example, a 70 kg runner may prefer a big bowl of oatmeal with 90 grams of carbohydrates if eating 2.5 hours before his run, but will only throw down a banana with 30 grams of carbohydrates if eating 30 minutes before a run. Suggested sources include, but are not limited to, oatmeal, toast with jam, English muffins, bananas, and rice. Experiment and take note of what works best for you.

DURING THE RUN

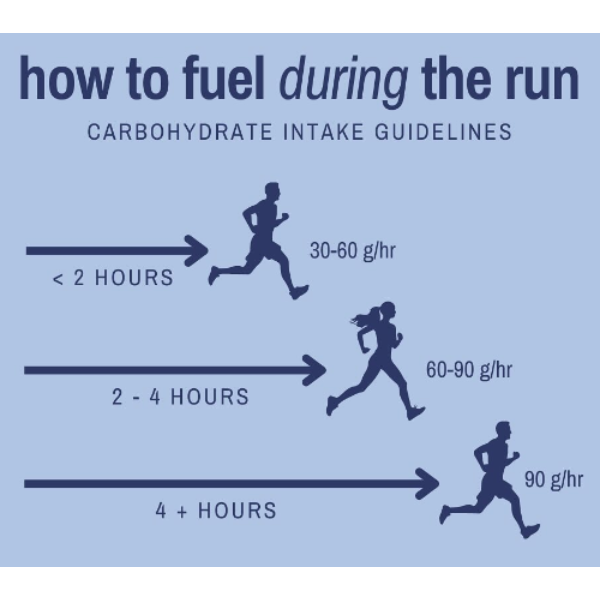

FUELING DURING THE RACE

For races lasting longer than 2 hours, regular consumption of calories is advised, with a starting point being 250-300 calories and 45-60 grams of carbohydrates per hour. Most runners take in about this amount, although some have worked up to 90 grams of carbohydrates per hour. To reach up to 90 grams without causing gastric upset involves consuming a mixture of multiple-transportable carbohydrates. A 2:1 ratio of glucose (60g) to fructose (30g) works best as the two sources of carbohydrates are absorbed at different rates and through different pathways. Protein ingestion of .25 grams per kg of bodyweight per hour is good for preserving protein balance and reducing muscle damage but that target may be a lot for some runners, so getting in even 5-10 grams per hour can be practical and still beneficial. Of all the macronutrients, I’d aim to prioritize optimal carbohydrate intake.

HYDRATING DURING THE RACE

A good starting point for determining your hydration needs is to aim to drink .5 - 1 liter (16-32 oz) of water per hour with 500-800 mg of sodium per liter. Keep in mind that your run food probably contains sodium as well and that should count toward your per hour target.

Salt tablets are not a recommended source of sodium as they can provide too much sodium and not enough water which may lead to overdrinking. Mixing electrolytes with water and eating slowly is probably the easiest way to make sure you are getting the right sodium-to-water ratio.

To get a more accurate idea of how much fluid is needed per hour, you can perform a sweat test. There are various ways to do this but the easiest is to weigh yourself nude before a 1 hour run at endurance pace (at a rate of perceived exertion of 5-6 on a scale of 1 to 10) and weigh yourself nude after. Between the two weigh-ins, don’t use the toilet or eat or drink anything. You then take the difference of the weights and aim to drink 90-95% of that amount per hour. (Some water is used for normal metabolic processes so we are not aiming to replace 100% of the water lost.) This figure gives you a fluid volume to experiment with on future runs of the same intensity and under similar environmental conditions. A more intense run and/or a hotter environment will probably require that you drink more.

Photo: Mikko Turunen / Kainuu Trail

PLANNING OUT FUELING NEEDS

In order to hit the recommended fueling targets and consume the optimal amount of carbohydrates per hour, you need to know your estimated time on the course and then calculate out how much food you will need to carry or how much you can put in a drop bag, if given the option. If you are planning on using the food supplied by aid stations, be sure that it’s enough and that it’s something you have tried and tested in training. Even if you don’t think you’ll need it, carrying some back up food can be a good idea in case things don’t go to plan.

When deciding on what food you will use, consider the terrain and temperature of the race. If possible, train in similar conditions (which is a good idea anyways) to make sure that the food is suitable and at least appealing enough that you will keep eating. You want to choose foods that won’t melt in hotter temperatures or freeze in colder temperatures. Your choices must also be easy to unwrap, chew, swallow, and digest while on the move. If possible, and this can depend a lot on the course and specific race logistics, have a variety of flavors and textures to choose from - especially important for runs lasting several hours. The longer the race, the more likely it is that you will experience flavor fatigue or eventually only want certain foods.

It is also important to cool down your body temperature during the race if the weather is hot (Photo: Mikko Turunen / Kainuu Trail)

SLOW AND STEADY EATING AND DRINKING

Eating and drinking on a timer can be a helpful strategy to make sure you are slowly and

regularly meeting your nutrition and hydration needs in a way that will be least likely to cause gastric distress. For example, if I’m aiming to eat a 260 calorie bar over the course of the next hour, I will think of it as 4 pieces and eat one piece every 15 minutes. If my goal is to drink about 750ml per hour, I’ll take a drink of water every 10 minutes which I’ve learned in training will be the frequency I need. This is not always executed perfectly and exactly on the minute but having this strategy in mind keeps me from getting behind on both hydration and nutrition. It can be tempting to avoid eating when I’m feeling great. At that moment, the last thing I want to do is break my flow and eat something, but I have to remind myself that the flow will be more like a drain if I don’t eat. It also may not be appealing to drink much in colder temperatures but it still is necessary.

It’s very difficult to catch up if you fall behind with nutrition and hydration. You’re also less likely to feel hungry or feel able to put food down later on into a race, which is all the more reason for eating sufficiently and as planned for as long as you can.

Iso-Valkeainen aid station at the Kainuu Trail 2023 (Photo: Mikko Turunen / Kainuu Trail)

CAFFEINE DURING THE RUN

Having caffeine through coffee or other supplementation before a race is common and can be beneficial for most runners as it reduces perceived fatigue. A morning coffee or two may have between 100-300 mg of caffeine which will last 2-3 hours, so additional supplementation may not be needed until after a few hours into a run. For ultras under 6 hours, 50mg per hour is practical. For longer races, especially if planning to run through the night, it may be better to wait until later to start supplementing with caffeine. Supplementation could come through gels or chews but it can also be beneficial to have 50mg tablets or capsules available for instances where caffeine is needed but extra calories are not. A person’s individual sensitivity to caffeine should be considered and of course usage should be trialed in long training runs.

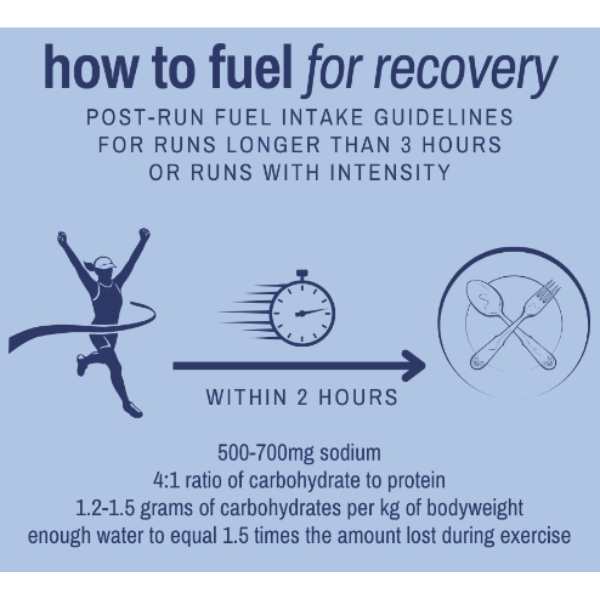

POST-RACE NUTRITION AND HYDRATION

It’s often advised to eat soon after finishing exercise for optimal recovery. While normal

balanced meals and rest throughout the following 24 hours will most likely allow for complete glycogen replenishment, the 30-60 minute window following exercise is when the body’s muscle cells are in the best state for glycogen replenishment. To optimize recovery and minimize post-exercise damage to muscles, post-race nutrition within 2 hours should be a 4:1 ratio of carbohydrate to protein, with ideally 1.2-1.5 grams of carbohydrate per kg of bodyweight. For the purposes of hydration, 500-700 mg of sodium should also be consumed with a quantity of water that is equal to 1.5 times the amount lost during exercise.

A simple way to get everything together, especially if you are not hungry, is to make a

post-workout smoothie with bananas, protein powder, perhaps electrolytes, and anything else that looks delicious and compatible. A 70 kg runner could blend some kind of dairy or plant milk with 2 bananas, 50 grams of uncooked oats (altogether roughly 100 grams of carbohydrates), and 1 scoop of protein powder (25-30 grams of protein). For something more filling, some healthy fat, perhaps from seeds or nuts, can be added.

In addition to optimizing immediate post-exercise nutrition, balanced meals that include carbohydrates, protein, and fat along with plenty of water should be consumed in the following 24 hours.

TEST IN TRAINING AND TAKE GOOD NOTES

As with all recommendations, you have to try these things on for yourself, make adjustments, and take good notes about what works and what doesn’t. There are a lot of variables that can contribute to a good or bad race nutrition strategy and it can be difficult to isolate the piece that needs to be changed. Good notes can help you notice trends and lead you to making more informed decisions about your fueling strategy.

I’d be interested in hearing if you found any of these points useful. Let me know if you have any feedback or questions!

Instagram: @runfar_liftheavy_

Email: jeremy.inabnit@runfarliftheavy.com

Website: runfarliftheavy.com

Jeremy at the finish in Kainuu Trail 2023. (Photo: Kainuu Trail)

REFERENCES & FURTHER READING:

1. Ivy, J. “REGULATION OF MUSCLE GLYCOGEN REPLETION, MUSCLE PROTEIN

SYNTHESIS AND REPAIR FOLLOWING EXERCISE” Journal of Sports Science and Medicine

(2004) 3, 131-138

2. https://www.slowtwitch.com/Features/Osmo_Nutrition_Test_3406.html Retrieved March 24, 2015.

3. International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: nutritional considerations for

single-stage ultra-marathon training and racing. (2019)

4. Richter EA, Derave W, Wojtaszewski JF.. Glucose, exercise and insulin: emerging concepts.

J Physiol (London). 2001;535(pt 2):313–322

5. Burke LM, van Loon LJ, Hawley JA.. Post-exercise muscle glycogen resynthesis in humans. JAppl Physiol. 2017;122:1055–1067.

6. Mikines KJ, Farrell PA, Sonne B et al. , Postexercise dose-response relationship between

plasma glucose and insulin secretion. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:988–999

7. Sherman WM, Doyle JA, Lamb DR et al. , Dietary carbohydrate, muscle glycogen, and

exercise performance during 7 d of training. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;57:27–31

8. Devlin BL, Leveritt MD, Kingsley M et al. , Dietary intake, body composition and nutrition

knowledge of Australian football and soccer players: implications for sports nutrition

professionals in practice. Int J Sports Nutr Exerc Metab. 2017;27:130–138

9. Burke LM, Hawley JA, Wong SH et al. , Carbohydrates for training and competition. J SportsSci. 2011;29(suppl 1):S17–S27.

10. Kenefick R, Cheuvront S, Leon L, O’Brien K. 2012. “Dehydration and Rehydration”

Wilderness Medicine, 6th Ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby.

11. Thomas, D. T., Erdman, K. A., Burke, L. M. (2016). American college of sports medicine jointposition statements. Nutrition and athletic performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc,

Mar;48,3:543-568.

12. Vitale, K. & Getzin, A. (2019). Nutrition and supplement update for the endurance athlete:review and recommendations. Nutrients, 11, 1289